Heralded as one the most beloved and well-known holy sites in Asia, Shwedagon Pagoda wows its spectators with its charming architectural design and shimmering gold plated dome that is topped wonderfully with a stupamade up of over 4,500 rubies, diamonds, topaz and sapphires. And by the way, this gleaming pagoda in Asia also boasts an imposing height of 325 feet.

8,688 solid gold plates make up the exterior of the Shwedagon Pagoda’s 320-foot stupa, topped off with more than 5,000 diamonds and about 2,300 rubies, sapphire and topaz. That the treasures remain untouched even in the midst of busy, bustling Yangon shows the kind of respect that the Shwedagon Pagoda commands.

The 2,500-year-old Pagoda houses relics from the past four Buddhas, including eight hairs from Gautama Buddha himself. Its unique location in Yangon ensures its domination of the city’s skyline.

Shwedagon also dominates Myanmar’s history; British bureaucrats’ refusal to remove shoes in its vicinity fed the discontent that eventually led to Burmese independence. More recently, the Pagoda’s monks played a central role in the aborted uprising of September 2007.

How to get there: Shwedagon is a key destination in the Myanmar city of Yangon. Most visitors fly into Yangon and take a taxi to visit Shwedagon.

พระเจดีย์ศักดิ์สิทธิ์ที่ประดิษฐานพระเกศาธาตุของพระพุทธเจ้า ศูนย์กลางความศรัธาที่พุทธศาสนิกชนชาวพม่าต้องมาสักการะสักครั้งในชีวิต ถือเป็นศาสนสถานอันเป็นที่สุด แห่งหนึ่งของอุษาคเนย์ ที่อร่ามไปด้วยทองคำและยอดเพชร 76 กะรัตที่เปล่งประกาย

Shwedagon Pagoda (unknown age, likely mid-late 1st millenium onward) (ရွှေတိဂုံဘုရား)

The Shwedagon Pagoda is the most sacred monument in Myanmar. Standing 99 meters high and sitting atop Singuttara Hill, the zedi (chedi, or stupa) is visible throughout Yangon and well into the surrounding countryside. Although the pagoda in its present form appears solid, immobile, and permanent, the history of the pagoda is almost the opposite: hazy, mutable, and obscure; built on foundations of fantastic myths and legends.

Mythological Origins

The mythological history of the Shwedagon extends back 2,500 years ago to the historical Buddha’s own lifetime in the 6th century BCE. A legend recounts that two merchants from Burma, Tapussa and Bhallika, met the Buddha in the northern Indian town of Bodh Gaya, which was destined to become a Buddhist pilgrimage site in the centuries to come. The merchants, overcome by the grace of the Buddha, offered him a meal of rice cakes and honeyed food—which in some versions of the tale, was the first meal the Buddha ate after attaining enlightenment. The Buddha then provided the merchants with a keepsake in return, offering them 8 strands of his own hair, which they gratefully accepted as holy relics. The merchants then returned to their homeland in Burma, bearing the relics, and were welcomed with great pomp and ceremony by King Okkalapa, the local ruler. The king then enshrined the relics in a zedi, creating the first incarnation of the Shwedagon.

Historian Donald Stadtner notes that this early myth drew on an obscure episode mentioned in the pali canon, the core texts of Theravada Buddhism. The earliest versions of the canon do mention two merchants of the same name, but they are said to have been from Ukkala, a former name of the present-day state of Orissa in eastern India. Later embellishment of the myth, associating the merchants with Yangon, took place as early as the 15th century, but possibly earlier.

Stadtner notes that the myth continued to expand in the 16th and the 17th centuries, with a text from the year 1588 mentioning further developments in the ‘history’ of the pagoda after the two merchants returned to their homeland. The text records that King Okkalapa initiated a search of Singuttara Hill, miraculously discovering a hidden underground chamber containing three relics of ancient Buddhas who had flourished in the mythological eons before the advent of the historical Buddha. These relics included a staff, water pot, and robe relic owned, respectively, by the Buddhas Kakusandha, Konagamana, and Kassapa. Each of these predecessors lived so long ago that the relics would have been millions, if not billions of years old, making their discovery in one location all the more auspicious. The grateful King then set about building the great Shwedagon—literally, the ‘Reliquary of the Four’ to house the three sets of relics alongside the hair relics brought by the two merchants.

The official history of the pagoda, as recorded on English-language pamphlets, is quite explicit that King Okkalapa built a cell at the center of the Shwedagon measuring 66 feet high to enshrine the relics. Whether any relic chamber exists will likely never be known, but as reliquaries have often been found in damaged zedi throughout Burma, there is probably a kernel of truth to the legend.

Documented History

Myth aside, it is impossible to determine the historical origins of the Shwedagon as the site has been built and rebuilt many times. Even the large zedi we see today probably encases earlier layers nested one another (this practice was relatively common; for instance the Kyauk-mye-mo-zedi-gyi stupa at Bagan is one of numerous such examples). Indeed, British troops in the 19th century attempted to bore a tunnel into the east face, discovering only a solid brick core surrounded by ‘seven casings’. Stadtner suggests that any relic chamber, should one exist, would probably hold relics similar to those found in the Botataung pagoda, which included one hair relic, bone fragments, and a number of votive terracotta plates.

According to Falconer et. al, the site of the Shwedagon was once waterlogged, as the Yangon river delta had not yet deposited enough silt to form the landscape that forms the Yangon area we see today. In prehistoric times the Singuttara hill was once an island, and as one of the highest points in the otherwise flat region, “the prehistoric occupants of the small fishing village that preceded the founding of Rangoon undoubtedly venerated the hill” (Falconer et al., p. 53). As Yangon gradually filled out in the centuries to come, the hill would have remained a focal point of devotion, and it is not unreasonable to assume that one or more small temples probably existed on the site long before the “Shwedagon” came into being. Stadtner concedes that “the stupa’s origins likely go back to the first millennium, but there is no firm proof in the absence of excavations and epigraphs” (Stadtner, p. 90).

The temple bursts onto the historical scene only much later, no earlier than the 14th century. A trilingual inscription written on the temple platform notes that King Banya U of the Hanthawaddy kingdom at Pegu (r. 1369-84) enlarged the pagoda to a height of 18.5 meters. His son, Rajadhiraja (r. 1385-1423) enlarged the pagoda still further and installed the spire. In the reign of the following King, Bannya Ramkuit (r. 1423-46), the pagoda was seriously damaged—probably by an earthquake—in 1436. By then the monument was sufficiently associated with the royal enterprise that he sent off his son and queen to oversee the reconstruction. Later in the same century, Queen Shin Sawbu (r. 1454-71) and her son-in-law King Dhammaceti enhanced the site still further with laterite terraces, stone lamps, coconut trees, and work on the pagoda itself. None of these improvements are visible today, though the terracing was clearly evident during the British occupation in the 19th century. Soldiers clearing the perimeter of the pagoda also found several artifacts associated with the 15th century work; unfortunately, all were taken to London and the most important item—a small gold reliquary in the shape of a stupa—disappeared in the 1950s after it was removed from the collection of the Victoria and Albert Museum. It likely still survives, though in the hands of an unknown private collector.

Kings continued to patronize the pagoda in the following centuries, most notably King Hsinbyushin (r. 1763-76), who was responsible for providing the pagoda with its current height and shape. As was common practice, he made a show of donating his own weight in gold (77 kilos) to gild the exterior. He also sponsored the construction of jewel-encrusted hti to crown his reconstruction efforts.

Although the pagoda survived the British occupation in the 19th and early 20th centuries, it was repeatedly deprecated by the occupiers. For instance, British troops first took control the pagoda during the 1st Anglo-Burmese war (1824-26). The occupiers, led by General Archibald Campbell, took the fortified pagoda in May 1824, in the process desecrating the compound by, among other indignities, not removing their footwear. In addition to the pagoda’s propaganda value (Aung-Thwin called it “the ‘palladium’ of the kingdom and therefore a symbolic slap in the face” (Aung-Thwin, p. 180), the British found the pagoda useful as a garrison due to its elevated position. Although the British returned Yangon to the Burmese at the conclusion of the campaign (in return for, among other things, a huge indemnity) the pagoda suffered a similar fate during the 2nd Anglo-Burmese War (1852-53) when the pagoda was again stormed by British soldiers in April 1852. Following the conclusion of hostilities, which were in Britain’s favor, the British retained control of all of lower Burma, and the Shwedagon remained in foreign hands.

Tensions rose again in November 1871 with the mounting of a new hti donated by King Mindon, the ruler of the remnants of the Konbaung kingdom. As Mindon held no political power over Lower Burma, which was entirely in British hands, the British were concerned that his presence in Yangon to observe the proceedings might precipitate a nationalist revolt. Although they ultimately allowed the work to proceed, Mindon’s representatives were not allowed to participate. The actual work was carried out under British supervision by subjects of Lower Burma. The new hti remained in place for well over a century until it was removed in April 1999 and replaced with a new one of stainless steel. The old hti remains on site, preserved in a platform on the east side of the pagoda.

Design

The Shwedagon is an archetypal Burmese-style zedi, or chedi, characterized by a wide, flaring base, a bell-shaped body, and a tall, tapering spire capped by a hti (umbrella finial). The zedi’s base is octagonal with redented edges, transitioning to circular bands 1/3rd of the way up. These in turn give way to the bell-shaped midsection (in Sri-Lankan fashion) topped with what is often described as an “inverted alms bowl”. From here, the shaft slowly tapers along a series of rings which give way to multiple ‘lotus-petal’ bands topped with a ‘banana bud’. As the banana bud tapers to a point, the hti covers the final few meters and is in turn topped with a vane and a diamond orb (the sein bu).

The zedi is gilded with gold, silver and copper plates that were often sponsored or donated by individuals seeking merit. Numerous jewels also bedeck the monument, with Stadtner noting that the very top of the monument holds “over 7,000 diamonds rubies, and sapphires attached to the vane and contained within the small orb-shaped object at the top” (Stadtner, p. 97). The vane alone weighs in at 419 kilograms and measures 130 centimeters in width, while the orb is 56 centimeters in diameter and contains 1,800 carats of fine diamonds.

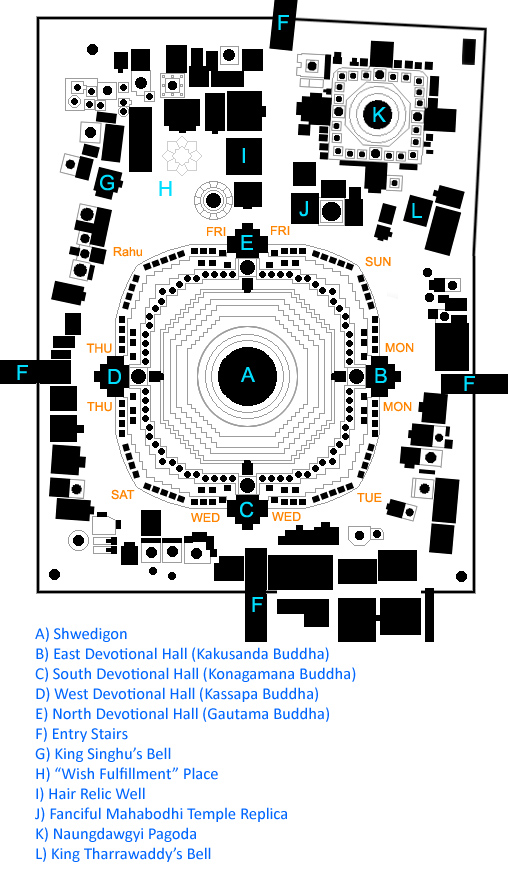

The main zedi is surrounded by 64 small stupas resembling miniature bells. These in turn are surrounded by almost a hundred square-shaped shrines located nearly at ground level. Each monument is associated with one of eight ‘planetary posts’ that corresponds to a particular planet, a specific animal, and a day of the week (Wednesday is given two posts, one for the morning and the other for the afternoon). Worshippers will typically begin their visit by praying at the planetary post corresponding to their birth date, then continue in a clockwise fashion around the ensemble.

In between the planetary posts are four devotional halls facing the cardinal directions. The design of each is idiosyncratic and all were built or refurbished at different times, though none of the halls (or for that matter any of the standing structures apart from the zedi) were built prior to the 1860s. The halls all feature tall pyat-that style roofs and are mainly composed of highly ornamented wood. As the Shwedagon was purportedly founded to enshrine the hair relics of Gautama Buddha, along with relics discovered from the prior three Buddhas, one hall is assigned to each of the four Buddhas.

The outermost periphery of the Shwedagon is a low parapet wall that completely surrounds the monument. It was built in 1999 during the last phase of major reconstruction at the Shwedigon. The top of the ledge is a convenient space for worshippers to light votive candles, while the outward-facing side of the ledge is fitted with over 500 tiles depicting the Jataka tales, the past lives of the Buddha.

The ensemble that comprises the Shwedagon, its gates, the planetary posts and subsidiary shrines all sits one what is often referred to as the middle terrace, a broad rectangular expanse of ground that designates the grounds of the temple. Many dozens of freestanding pavilions are scattered across the ground in no apparent order, though most are clustered at the edges of the middle terrace so as to leave room for worshippers circum-ambulating the chedi.

Access to the middle terrace is provided by a number of entrances, chief among which are four sets of stairways facing the cardinal directions.

Plan of the Shwedagon

Redrawn composition by Timothy M Ciccone following tourist pamphlets and notes/photographs on site. Note that the ‘planetary posts’ around the perimeter (shown in orange) do not move chronologically, as the position of each day/time corresponds to a nine-square diagram with Wednesday evening/Rahu in the top-left and Tuesday in the southeast. Each direction is associated with a particular day, planet, and animal.

Location

Bibliography

All images copyright 2017 by Timothy M. Ciccone and Abraham Chiwon Ahn. Photographed July 2017.

Falconer, John et al. Burmese Design and Architecture. Singapore: Tuttle Publishing, 2000.

Fraser, and Donald M. Stadtner. Buddhist Art of Myanmar. New Haven: Asia Society Museum in association with Yale University Press, 2015.

Fraser-Lu, Sylvia. Splendour in Wood. New York: Weatherhill, 2001.

Moore, Elizabeth T. Early Landscapes of Myanmar. Thailand: River Books, 2007.

Pichard, Pierre. Inventory of the Monuments at Pagan Vol V: Monuments 1137-1439. Paris: UNESCO, 1993.

Stadtner, Donald. Sacred Sites of Burma. Bangkok: River Books, 2008.

Strachan, Paul. Imperial Pagan. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1990.

Tettoni, Invernizzi. Myanmar style : Art, Architecture and Design of Burma. London: Thames & Hudson, 1998.

Thaw, Aung. Historical Sites in Myanmar. Myanmar: Ministry of Religious Affairs and Culture, unknown publication date.

Thanegi, Ma. Myanmar Architecture. City: Times Editions – Marshall Cavendish, 2005.

https://www.orientalarchitecture.com/sid/520/myanmar